To Rebuild Windows, Microsoft Razed Walls

Three-Year Effort to Create Latest Version Meant Close Collaboration Among Workers to Avoid Vista's Missteps

To build its new operating system, Microsoft Corp. needed to do more than fix the flaws of its predecessor. The company also had to address major bugs in its software development process.

The three-year effort to create Windows 7, which lands on store shelves this Thursday, was marked by closer collaboration between the thousands of people working on aspects of the high-stakes product—reducing communications breakdowns that contributed to delays and defects in Windows Vista, one of the company's biggest missteps.

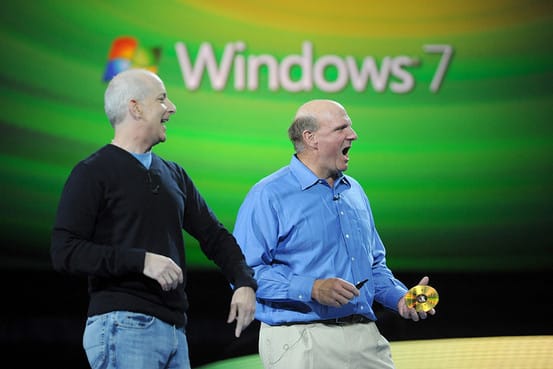

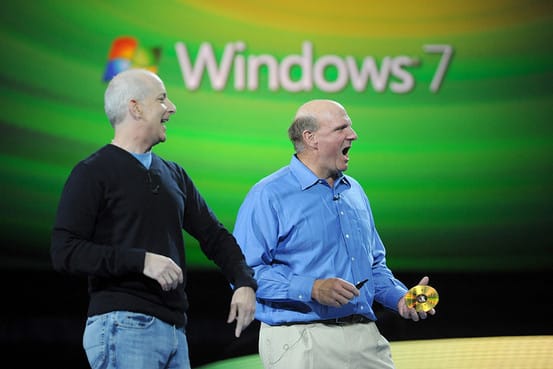

Steve Ballmer, Microsoft's chief executive, also directed that software developers work more closely with computer makers, including Hewlett-Packard Co., and other PC players to head off the kinds of problems that hobbled Vista.

It's too soon to tell how well the effort worked. But favorable early reviews for Windows 7 have restored some faith that the software giant can still execute in a business that accounted for more than half of the company's $20.36 billion in operating income during the fiscal year ended June 30.

"I think Microsoft knew with Windows 7 it had to work harder and right some wrongs," says Richard Barton, a Seattle entrepreneur who worked at Microsoft on Windows and other products during most of the 1990s. "It looks like they are."

One of Microsoft's rivals, Apple Inc., believes Windows 7 will create an opening for it to lure more customers to the Macintosh, in part because of the tedious process required to upgrade to Windows 7 from PCs running Windows XP.

Philip Schiller, Apple's senior vice president of world-wide product marketing, says it's not clear whether Windows 7 has overcome the flaws of its predecessor. "A lot of the same things were said about Vista before it shipped," Mr. Schiller says. "I think we need to wait and see if it's all that much better."

The Windows 7 development was led by Steven Sinofsky, a 20-year Microsoft veteran who had worked in its Office group until 2006. It's a process that he compares to an epic home remodeling project. "Windows is no different—it's a kitchen for a billion people," he says.

Two of Vista's biggest failings were that it took too long to make—five years—and crucial software for powering printers, graphics cards and other hardware wasn't ready when the operating system shipped, so early Vista customers couldn't use many of those devices with their computers.

A key problem was that the Windows team had evolved into a rigid set of silos—each responsible for specific technical features—that didn't share their plans widely. The programming code each created might work fine on its own, but cause technical problems when integrated with code created by others.

"That's where the conflicts started," says Julie Larson-Green, a corporate vice president who worked in the Office group with Mr. Sinofsky. With Windows 7, Mr. Sinofsky and Ms. Larson-Green pushed developers to share their plans widely and to think more broadly about the experience of using a PC.

That approach helped the Windows 7 team stick to an important new objective called "quieting the system," which sought to minimize windows and dialogue bubbles—such as security warnings—that pop up on screen during the normal operation of the PC. Such annoying messages became one of the most maligned aspects of Vista.

In Windows 7, Microsoft reduced those messages to make users feel more in control and comfortable, says Linda Averett, a Microsoft group program manager who was a chief enforcer of the system-quieting effort. "Every group knew that was part of the plan," says Ms. Averett. "So when I came calling, they weren't surprised and we were able to actually make it work."

Microsoft collaborated more closely with its hardware partners, too. H-P and Microsoft assigned teams to do a "deep dive into the guts" of H-P machines to figure out how to speed up the time it takes to start and shut down Windows 7, says John Cook, H-P's vice president of desktop marketing. "With Vista, that never worked," he adds.

Mr. Cook says H-P and Microsoft "had some brutally honest discussions with what our engineers and customers thought of Vista....They listened and were much more humble."

Microsoft's new approach also helped the company add slick new features. They include advances on a technology called "multi-touch" that lets users issue commands while touching specially equipped display screens with multiple fingers.

Vista offered a version of touch-sensing that was mainly a direct substitute for a computer mouse. With Windows 7, in contrast, the software responds differently when it senses a user is touching a screen, spacing icons differently and making scroll bars larger to fit the dimensions of fingers—something that required touch engineers to work closely with all of the major Windows 7 groups, says Ian LeGrow, a Microsoft group program manager.

"Instead of it being a plan owned by one team, our plan was a part of all the teams," says Mr. LeGrow, who led touch technology on the Windows 7 team.

—Pui-Wing Tam contributed to this article.

Write to Nick Wingfield at [email protected]

- Wall Street Journal

Three-Year Effort to Create Latest Version Meant Close Collaboration Among Workers to Avoid Vista's Missteps

To build its new operating system, Microsoft Corp. needed to do more than fix the flaws of its predecessor. The company also had to address major bugs in its software development process.

The three-year effort to create Windows 7, which lands on store shelves this Thursday, was marked by closer collaboration between the thousands of people working on aspects of the high-stakes product—reducing communications breakdowns that contributed to delays and defects in Windows Vista, one of the company's biggest missteps.

Steve Ballmer, Microsoft's chief executive, also directed that software developers work more closely with computer makers, including Hewlett-Packard Co., and other PC players to head off the kinds of problems that hobbled Vista.

It's too soon to tell how well the effort worked. But favorable early reviews for Windows 7 have restored some faith that the software giant can still execute in a business that accounted for more than half of the company's $20.36 billion in operating income during the fiscal year ended June 30.

"I think Microsoft knew with Windows 7 it had to work harder and right some wrongs," says Richard Barton, a Seattle entrepreneur who worked at Microsoft on Windows and other products during most of the 1990s. "It looks like they are."

One of Microsoft's rivals, Apple Inc., believes Windows 7 will create an opening for it to lure more customers to the Macintosh, in part because of the tedious process required to upgrade to Windows 7 from PCs running Windows XP.

Philip Schiller, Apple's senior vice president of world-wide product marketing, says it's not clear whether Windows 7 has overcome the flaws of its predecessor. "A lot of the same things were said about Vista before it shipped," Mr. Schiller says. "I think we need to wait and see if it's all that much better."

The Windows 7 development was led by Steven Sinofsky, a 20-year Microsoft veteran who had worked in its Office group until 2006. It's a process that he compares to an epic home remodeling project. "Windows is no different—it's a kitchen for a billion people," he says.

Two of Vista's biggest failings were that it took too long to make—five years—and crucial software for powering printers, graphics cards and other hardware wasn't ready when the operating system shipped, so early Vista customers couldn't use many of those devices with their computers.

A key problem was that the Windows team had evolved into a rigid set of silos—each responsible for specific technical features—that didn't share their plans widely. The programming code each created might work fine on its own, but cause technical problems when integrated with code created by others.

"That's where the conflicts started," says Julie Larson-Green, a corporate vice president who worked in the Office group with Mr. Sinofsky. With Windows 7, Mr. Sinofsky and Ms. Larson-Green pushed developers to share their plans widely and to think more broadly about the experience of using a PC.

That approach helped the Windows 7 team stick to an important new objective called "quieting the system," which sought to minimize windows and dialogue bubbles—such as security warnings—that pop up on screen during the normal operation of the PC. Such annoying messages became one of the most maligned aspects of Vista.

In Windows 7, Microsoft reduced those messages to make users feel more in control and comfortable, says Linda Averett, a Microsoft group program manager who was a chief enforcer of the system-quieting effort. "Every group knew that was part of the plan," says Ms. Averett. "So when I came calling, they weren't surprised and we were able to actually make it work."

Microsoft collaborated more closely with its hardware partners, too. H-P and Microsoft assigned teams to do a "deep dive into the guts" of H-P machines to figure out how to speed up the time it takes to start and shut down Windows 7, says John Cook, H-P's vice president of desktop marketing. "With Vista, that never worked," he adds.

Mr. Cook says H-P and Microsoft "had some brutally honest discussions with what our engineers and customers thought of Vista....They listened and were much more humble."

Microsoft's new approach also helped the company add slick new features. They include advances on a technology called "multi-touch" that lets users issue commands while touching specially equipped display screens with multiple fingers.

Vista offered a version of touch-sensing that was mainly a direct substitute for a computer mouse. With Windows 7, in contrast, the software responds differently when it senses a user is touching a screen, spacing icons differently and making scroll bars larger to fit the dimensions of fingers—something that required touch engineers to work closely with all of the major Windows 7 groups, says Ian LeGrow, a Microsoft group program manager.

"Instead of it being a plan owned by one team, our plan was a part of all the teams," says Mr. LeGrow, who led touch technology on the Windows 7 team.

—Pui-Wing Tam contributed to this article.

Write to Nick Wingfield at [email protected]

- Wall Street Journal